Music has long brought Southerners together, whether it be in bars and dance halls or in churches and revivals. In this essay, the writer recalls her family’s musical roots and how she reconnected with them in the 1970s as a college student, during a time when the old ways – and the myths and narratives that accompanied them – were diminishing and disappearing.

Songlines

by Karen Luke Jackson

Music . . . is a memory bank for finding one’s way about the world.

— Bruce Chatwin

Spirits of ancestors often dwell near homeplaces and in graveyards, but in my family, they can be found in Mystic, Georgia, a small community about ten miles off I-75. There a memorial marks an event that took place for eighty-five years—a singing convention founded by my mother’s grandfather William Jackson Royal.

“Uncle Billy,” that’s what nearly everyone called him, died singing. On May 24, 1931, he had a heart attack while leading a hymn at the Irwin County High School commencement sermon. People sat in their pews and sang “Nearer My God to Thee” while men carried his body down the aisle.

“His funeral was held at the tabernacle,” Mama recalled as we drove to the cemetery forty years later to visit his grave. It was 1970, and I needed to document the date of his death to complete a college research paper I was writing at Valdosta State. She was thrilled I was preserving a bit of family history, so I’d asked her to come along.

“I’ve been told more than two thousand people passed by his casket to pay their respects,” Mama said.

“That’s what the newspaper reported,” I confirmed.

***

Influenced by William Walker’s 1866 Christian Harmony, Uncle Billy preferred do re mi, the seven-note European system of musical notation, to the Sacred Harp fa sol la. From 1875 until 1930, he traveled on horseback as far north as Macon, Georgia, and as far south as Jacksonville, Florida, teaching folks how to “read” music using geometric shapes that represented tones on a scale. Students paid ten cents a day to attend classes. His week-long singing schools often concluded with programs designed to showcase what pupils, children and adults alike, had learned.

In 1893, when my great grandfather founded a convention in his home county of Irwin, local leaders insisted it bear his name. Churches hosted the Royal Singing Convention until crowds grew so large that people hung from open window sills and spilled out sanctuary doors. Then the event met under a circus-like tent. In 1919, a tornado destroyed the canvas shelter. The sing moved into a nearby warehouse. The next year, families raised more than five thousand dollars to purchase land in Mystic and erect the open-air tabernacle where my grandfather’s funeral was later held.

Growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, I’d spent third Sunday weekends in July listening to that edifice come alive with gospel song.

* **

“There will be a happy meeting in heaven, I know . . .”

Sopranos rang out. Altos joined in. Uncle Erston, dapper in his white suit and wing-tipped shoes, sat at a small writing desk on the elevated stage, next to the solo piano. The “Good Indian,” as my sister Janis and I called him, visited from his home in Florida twice a year: in July to preside over the convention, a role handed down from his grandfather to his father to him, and at Thanksgiving to hunt with Uncle James. That’s when he brought navel oranges. Bearing fruit for pilgrim relatives garnered him his nickname.

Cooling his face with a Paulk Funeral Hone fan and tapping his feet to the music’s beat, Uncle Erston was one of the few Royals who couldn’t carry a tune. Even Daddy, an in-law, had a quartet and sang lead.

My sister Janis and I perched on plank benches in the audience. Barelegged, we were careful to avoid splinters. Our toes scratched designs in the dirt floor.

“That will be a happy meet-ting da-ay.”

“Next singer up is Cary Hilliard from Rhine, Georgia,” Uncle Erston boomed, “and after him, Bertha and Shorty Bethea.”

My sister and I glanced at one another. Before the next song began, we made our escape. Outside, hot dog and soft drink vendors hawked refreshments. Spending-money, fifty cents, burned our shorts’ pockets. Coca-Colas in frosty green bottles floated in melting ice. They cost twenty-five cents, snow cones only a dime. My sister and I headed for the shaved ice. She ordered cherry. I chose grape. Red and purple streaked our cheeks, stained our shirts. But no one objected in the blistering heat.

After treats, we caught up with cousins playing tag beneath live oaks. “That’s our great-grandfather,” Seaborn, the oldest, said pointing toward a bronze bust. I tilted my head to look. “You’re it,” he hollered as he tagged my arm.

***

Those sweltering Mystic afternoons floated from my head as I pulled my purple Dodge Dart off the road and parked on the shoulder in Bermuda grass that begged to be mowed.

“I was only eight when Granddaddy Royal died,” Mama recalled, “but after the service at Mystic, we hauled his body back here to Frank. Took us all day in that horse and buggy.”

“Roll down your window, Mama,” I reminded as she reached for her door handle, “a good inch or two so the heat can escape.”

She obliged and exited the car. “It’s over there,” she said, pointing toward mottled tombstones in the southwestern corner. As we walked toward the grave, gnats swarmed our faces. Swatting them away, I glanced at my mother and spied a sheepish grin.

“Did I ever tell you that Granddaddy Royal was thrown out of the church?”

“No. Daddy always said the man didn’t have a pot to pee in, but people from the Frank community fought over who was going to drive him to the next sing.”

“They did. But he was known to take a nip or two and belonged to a secret order. The deacons said either one was good ’nuf cause.”

I took out my notebook to jot down the new information. Mama gulped.

“You’re not going to put that in your paper, are you?” she said, backpedaling as fast as she could. “I’m pretty sure they reinstated him later.”

Sometime the following week, I found an article in the Ocilla Star documenting that Masons—the secret order—conducted my great-grandfather’s graveside rites. That detail appeared in my final paper. The story about his being turned out of a church did not.

***

After I moved to North Carolina in 1971, I returned each July to be part of that annual gathering, to help feed more than two hundred singers at the dinners-on-the-ground, to stay up half the night chatting with musicians who bedded down at my parents’ home, in chairs, on couches, air mattresses spread on the floor. Singers from Florida, Alabama, South Carolina, and towns all over Georgia. They’d cluster around the piano in the basement and croon until two AM as if they couldn’t get enough time together, as if they knew the convention had a terminal illness and they dared not miss a single beat.

In the mid-’70s, the convention’s trustees faced significant challenges. The tabernacle’s network of posts, beams, and rafters supporting the roof needed extensive repairs. The number of singing teachers and song leaders had declined as gospel quartets had gained in popularity. Also, many people preferred entertainment in air-conditioned spaces rather than sitting on backless benches, fanning shirts that clung to their skin.

In July 1977, with Uncle Erston still at the helm, the convention convened for its last time. Among the attendees was a folklorist from the Smithsonian, videoing the proceedings, interviewing audience members, and recording songs. Older women reminisced about new dresses they’d worn to the event when they were teens and how they’d met their spouses there. Men spun stories about politicians who, between songs, had solicited their votes, including Herman Talmadge, former Governor of Georgia.

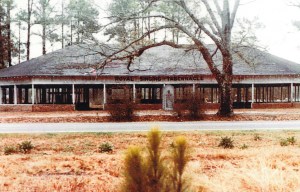

After that, the tabernacle stood a silent sentinel to a bygone era. Fearing it a safety hazard, trustees had the wooden structure demolished, leaving the bronze bust of Uncle Billy, sculpted in 1953 by Marshall Daugherty, to preside over the vacant site.

***

I don’t remember where we were or what we did that first July there was no convention, but I do remember Mama and I went away, probably to the beach as that was her healing place. Although she knew the convention had “run its course,” she grieved its demise on her watch. Losing the convention meant losing her way in the world.

Nor do I know how the idea of a monument to perpetuate the historical significance of that sacred place began to form. Someone contacted Stanford Anderson, a nationally-known architect who taught at MIT. He’d married into the family, and, although he knew little about the convention, agreed to design a memorial. Daddy helped Mama marshal stories, write newspaper articles, and raise funds.

On the third Sunday in July 1991, I attended the dedication with my parents, children, local dignitaries, and Anderson. Low brick walls outlined the structure’s original footprint. Granite cubes marked where posts had supported the roof, and interpretative panels stretched across the front where a stage had once hosted singers. We sat in webbed folding chairs, straw hats covering our heads, fanning away the heat. There were no snowballs or cokes in glass bottles, but the celebration, singing, and feasting, which moved to a nearby air-conditioned church, continued into the evening.

Daddy said more than once that marrying into Mama’s family saved him. Perhaps that’s why he was so determined to help keep the memory bank of that convention alive.

Today, my parents and sister rest in the cemetery where Uncle Billy is buried, but I feel them most near when I visit Mystic. There I walk the path of donor bricks etched with names of singers now deceased and titles of hymns I knew as a child. In that spot, I recall caramel cakes my mother baked to feed the crowd and how that annual sing marked me as a member of the Royal clan. Sometimes I pause beside the bust and listen to the songlines that I wish my children could hear.

Karen Luke Jackson’s publications include short stories and poems in numerous journals, two poetry collections, The View Ever Changing and GRIT, and The Story Mandala: Finding Wholeness in a Divided World, a book of essays co-edited with Dr. Sally Z. Hare. A native of South Georgia and a retreat leader with the Center for Courage & Renewal, Karen now resides in a cottage on a goat pasture in Western North Carolina. There, she writes and companions people on their spiritual journeys.

Lesson Plan: NH-MSF Lesson Plan Personal Narrative

Thanks for this interesting bit of history. My husband’s grandfather Little Jim Roberts sang at the Tabernacle and his mother Georgia Hilton occasionally played the organ there. Love reading about more of the history!

LikeLike

Karen, What an INTERESTING family tradition and history! It’s a gift to all of us that you have recorded and published it.

LikeLike