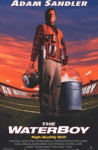

It was twenty-five years ago today that the cult classic The Waterboy was released. Set in swampy rural Louisiana, the 1998 film introduced us to Bobby Boucher, the hard-hitting momma’s boy who was urged on by the refrain “You can do it!” Playing opposite Adam Sandler’s stammering and consistently uncertain Boucher was Jerry Reed’s conniving bully of a coach Red Beaulieu. An infamous Southern character himself, Reed is, of course, famous for playing trucker Cletus Snow – the Snowman – in 1977’s Smokey and the Bandit. Though this film is known for its zany, off-color, and sometimes bizarre humor, The Waterboy also feeds the American appetite for narratives that reinforce common beliefs about rural Southerners: certainly, they must be stupid, backward, and downright weird.

It is probably important to make one thing clear before getting too far into the argument I am making here: I seriously doubt that Adam Sandler was trying to make a film of social commentary or to achieve something like documentary truth. His movie is clearly a comedy, and an absurd one, which wants to center itself on a lighthearted motif about a guy who triumphs over his circumstances. There are no deep moral conundrums to ponder here. Bobby Boucher lives with his overbearing mother, he tries to do a good work in his thankless job, and the girl he would like to have a relationship with is both out of his league and unsuitable to his mother. The guy can’t win— then he does. Bobby Boucher is an underdog by anyone’s definition, and we want to see him overcome all of this, to become a man, to be appreciated, to get the girl, all the things.

On the other hand, it is the distortions of Southern culture that provide the basis for this underdog status. Certainly we see that he dresses badly, stammers with nervous insecurity, and hyper-focuses on the insignificant task of filling cups with water. But who are the people antagonizing Bobby Boucher? An overprotective mother who manipulates her son to hide her own failures, a mean football coach who cheats and lies to win games, and a bunch of mean football players who torment the guy who makes sure they have water. To start with, Bobby’s mother is the Southern mom gone wrong. This isn’t the tirelessly loving woman we hear about in Johnny Cash’s songs. This one lives back in the swamp, tells strange lies, won’t listen to reason, refuses to allow her son to have opportunities, and rebukes the only girl who likes her son. Looking beyond her, Coach Red Beaulieu is the epitome of a big fish in a small pond. Football coaches in the South are often held up as mythic figures, and Sandler uses that aspect of the culture to create his villain. This football coach is not a legitimately good coach but wins with a stolen playbook. He coaches at a tiny local institution that lacks prestige, and he misuses his power by bullying people. Beyond him, we have the players on both teams that Bobby Boucher works for. These guys are not heroes of the gridiron. They are meatheads – some are overtly stupid, one is cross-eyed – who use their status on campus to abuse powerless people.

Beyond those three, we have other characters who evolve out of Southern myths. Bobby’s love interest Vicki Vallencourt is a modernized version of an Erskine Caldwell vixen. The only guy who is consistently supportive and kind toward Bobby is also one of the only black people in the story, a nod to the Changing South narrative in the late 1990s. The two devoted fans in the stands, played by Rob Schneider and Clint Howard, are clownish caricatures of backwater Cajuns. The Colonel Sanders science professor is an allusion that combines the mythic Southern academic with the pop-culture imagery of an imagined Civil War-era aristocrat. Rounding them out, we have Farmer Fran, the ever-smiling assistant coach who wanders around in overalls and a straw hat muttering in a pidgin dialect that no one understands. The only remarkably un-Southern character here is Coach Klein, the self-made loser who Bobby saves from his own neurotic insecurities. (Henry Winkler didn’t even bother to fake a bad accent.)

Beyond those three, we have other characters who evolve out of Southern myths. Bobby’s love interest Vicki Vallencourt is a modernized version of an Erskine Caldwell vixen. The only guy who is consistently supportive and kind toward Bobby is also one of the only black people in the story, a nod to the Changing South narrative in the late 1990s. The two devoted fans in the stands, played by Rob Schneider and Clint Howard, are clownish caricatures of backwater Cajuns. The Colonel Sanders science professor is an allusion that combines the mythic Southern academic with the pop-culture imagery of an imagined Civil War-era aristocrat. Rounding them out, we have Farmer Fran, the ever-smiling assistant coach who wanders around in overalls and a straw hat muttering in a pidgin dialect that no one understands. The only remarkably un-Southern character here is Coach Klein, the self-made loser who Bobby saves from his own neurotic insecurities. (Henry Winkler didn’t even bother to fake a bad accent.)

Maybe you’re asking the question by now: does this amount to the movie being offensive, or is it just good-natured comedy? In some ways, the jokes really are underpinned by a meanness toward Southern culture, an approach that says, This is what we think Southerners are like. If the attitude was different, a creative person like a filmmaker would shy away from these presentations and portrayals. On the other hand, the art of comedy is about exaggeration and distortion, so getting the jokes is probably easier if you are or ever have been a Southerner. I imagine that there are people from Vermont or Colorado who watched The Waterboy and wondered, Why is that funny . . . ? For my part, I wish these weren’t the myths and narratives that comedians and filmmakers have had to work with. But they are. And this film uses them to create a story about a guy from Louisiana whose unlikely gifts help him to transcend his lowly status without compromising what he finds important. In the end, Bobby Boucher has it all. He is a star football player who marries Vicki with his mother’s blessing and drives off on his trusty lawnmower . . . but not before Mama deals with one last Southern stereotype— his deadbeat dad.

Reviewed by Foster Dickson, editor of Nobody’s Home

One thought on “Review: “The Waterboy” (1998)”