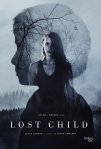

The 2017 folk horror film Lost Child tells the story of a military veteran who returns to her family home in the rural area of the Ozarks, where she encounters a boy who wanders out of the woods. The young woman Fern is suffering from PTSD after her service and comes home to a slate of old problems: her drug-addicted parents are dead, the mostly abandoned house is in disrepair, and her brother is using drugs now. Adding to the tension is the appearance of Cecil, a child of probably eight or nine, who locals warn her is a tatterdemalion. These evil spirits disguise themselves as children to work their way into a person’s life and wreak havoc. And some of the problems that Fern faces, like inexplicable natural phenomena and physical ailments, seem to imply that the boy might actually be what people say he is.

Unlike monster movies, slasher films, or other types of horror stories, the folk horror sub-genre derives its tension from the everyday and even the mundane. Setting aside the magical realism that is often employed to catapult the situation into the mythic, the events could usually happen. (Think Little Red Riding Hood: other than a talking wolf, the tale is about real dangers that face unaccompanied children.)

What we have in Lost Child is the juxtaposition of elements that can’t be explained: how does a child survive in the woods, where did he come from, and why do strange things happen when he’s around? But the situation must be dealt with. A homeless, neglected child can’t be ignored, and a veteran with PTSD can’t ignore her symptoms. The local community in this story answers the questions with an oversimplified response that allows bystanders to move on, not deal with it, and avoid taking responsibility: he’s not actually a boy, he’s an evil spirit. Fern doesn’t have that luxury, since it’s her house where Cecil keeps showing up. Fern has enough problems – some of them severe – and she also has a battle-hardened soldier’s capacity to deal with the harshest reality. Yet, the last thing she needs is a child to take care of, while coming to terms with her parents’ deaths, her brother’s addiction, and the after-effects of her experiences in the war. Despite that, there he is.

The story in Lost Child places mythic questions in the context of a modern Southern scenario: the drug addiction crisis in the rural South. Fern has escaped her parents’ and brother’s fate by joining the military, but it has not come without a cost. In dealing with Cecil and with her other trials, Fern receives little to no assistance from ordinary people in the local community, but does find some aid with a handful who stray from the norm. Ultimately – spoiler alert! – the boy’s presence can be explained by the discovery of his now-dead father’s home/encampment deep in the woods and, in the case of her physical symptoms, by natural science. The boy is not an evil spirit but has emerged from the forest because his only means of support is gone, and he showed up at the same time that certain flowers were blooming.

The story in Lost Child places mythic questions in the context of a modern Southern scenario: the drug addiction crisis in the rural South. Fern has escaped her parents’ and brother’s fate by joining the military, but it has not come without a cost. In dealing with Cecil and with her other trials, Fern receives little to no assistance from ordinary people in the local community, but does find some aid with a handful who stray from the norm. Ultimately – spoiler alert! – the boy’s presence can be explained by the discovery of his now-dead father’s home/encampment deep in the woods and, in the case of her physical symptoms, by natural science. The boy is not an evil spirit but has emerged from the forest because his only means of support is gone, and he showed up at the same time that certain flowers were blooming.

Lost Child relies on old narratives about society’s outsiders to turn the tables and challenge those existing narratives. Cecil is the helpless child of a drug-addicted parent, who had them living in squalor away from the rest of society. As a result, because Cecil could not be accounted for using normal means, it was assumed that his presence was unnatural, even evil. He had no social skills – being a child and having no education – and his little bit of instruction on how to live included maintaining secrecy at all costs. This is common among Southerners who live in rural and mountainous places, and the boy was behaving as he was taught to. However, what both he and Fern must face is the widespread tendency to base beliefs on myths, the ones that we use to demonize what we don’t understand or don’t want to face.

Reviewed by Foster Dickson, editor of Nobody’s Home