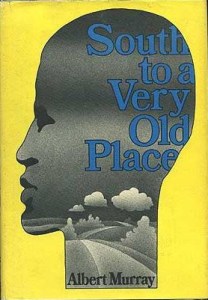

In the post-Civil Rights era, the visiting-the-New-South book emerged, and Albert Murray’s South to a Very Old Place may have been the first of its kind. Published in 1971 on the heels of The Omni-Americans, it preceded books like VS Naipaul’s A Turn in the South (1989), Eddy Harris’s South of Haunted Dreams (1993), and Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic (1998) by a long shot. Murray was raised in small black communities north of Mobile, Alabama, which include the now often-discussed area of Africatown. (He actually writes in this book about the Clotilde and how chemical plants had taken over the landscapes where he played as a boy.) Coming from nearly all-black communities that had a vibrant culture, Murray’s narrative of what it was to be a black Southerner differs significantly from commonly endorsed portrayals that focus on racism, injustice, and their effects. Instead, the narratives in his nonfiction, novels, and criticism are notable for their full-throated and vigorous portrayals that use colorful language to evoke a spirit of down-home willfulness in a culture whose beliefs forbade self-pity and emphasized the necessity of overcoming harsh and unfair circumstances.

In the post-Civil Rights era, the visiting-the-New-South book emerged, and Albert Murray’s South to a Very Old Place may have been the first of its kind. Published in 1971 on the heels of The Omni-Americans, it preceded books like VS Naipaul’s A Turn in the South (1989), Eddy Harris’s South of Haunted Dreams (1993), and Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic (1998) by a long shot. Murray was raised in small black communities north of Mobile, Alabama, which include the now often-discussed area of Africatown. (He actually writes in this book about the Clotilde and how chemical plants had taken over the landscapes where he played as a boy.) Coming from nearly all-black communities that had a vibrant culture, Murray’s narrative of what it was to be a black Southerner differs significantly from commonly endorsed portrayals that focus on racism, injustice, and their effects. Instead, the narratives in his nonfiction, novels, and criticism are notable for their full-throated and vigorous portrayals that use colorful language to evoke a spirit of down-home willfulness in a culture whose beliefs forbade self-pity and emphasized the necessity of overcoming harsh and unfair circumstances.

Next to The Hero and the Blues, South to a Very Old Place is probably Murray’s best-known book, though I came to his work first through a now out-of-print collection of criticism and speeches titled From the Briarpatch File. As another side note of my own, I’ll add that his semi-autobiographical Train Whistle Guitar is one of the liveliest novels I’ve ever read. So, I was coming to this book as a fan already – of Murray himself and of his ideas – and oddly enough, I have come to his famous books after admiring his lesser-known works first.

South to a Very Old Place opens not in the South, but in New York City and New Haven, Connecticut, where Murray was living when he began this project. Amid references to the “A” Train and 125th Street, he tells his reader:

But then, going back home has probably had as much if not more to do with people as with landmarks and place names and locations on maps and mileage charts anyway. Not that home is not a place, for even in its most abstract implications it is precisely the very oldest place in the world.

What he will explore here is the “fundamental interrelationship of recollection and make-believe” as it relates to what anyone considers “home”— in some sense, this is an exploration of a personal mythology. Furthermore, about two pages over, he lets us know “that being back is always the same as being where you wish to be.” In this brief preface-like chapter titled “New York,” we pick up a tone that is positive and energetic and sentiments that show how Murray is looking forward to revisiting his past in the South. I mention this, and make a point of it, because of its marked differences from the later books, like Eddy Harris’s South of Haunted Dreams, which begins with the ominous imagery of racism and a defiant tone.

But Albert Murray will be glossing over neither the difficult history of the South, nor the overarching racism that threatens any black man who lives there. In his second chapter, “New Haven,” which is framed by a narrative about taking the train up to Yale, Murray alludes to Faulkner’s classic character Quentin Compson in describing his notions of Southern whites: “You’re right, they’re fine folks. But you can’t live with them.” Then a few sentences down, he adds: “You got to know how to handle them; you got to outthink them, you got to stay one jump ahead of them.” Readers familiar with Murray’s work will recognize this idiom, which is reminiscent of the jackrabbit metaphor.

In this second chapter, Murray is writing about two giants of Southern cultural studies: the historian C. Vann Woodward and the writer Robert Penn Warren. The first of the two, Woodward, was a shining star at this moment. His 1955 book The Strange Career of Jim Crow and 1960’s The Burden of Southern History, now classics in their field, were fairly recent releases in 1970. Murray calls Woodward “that downhome-raised historian” but doesn’t seem fond of the man’s ideas, liberal and righteous as he was considered in his heyday. About Warren, Murray weaves in and out of his work, alluding to works and passages and ideas in a way that it isn’t fully clear how he feels about it. Ultimately, my sense of the chapter is that, before this Southerner left the North for his visit back home, he used these two prominent white Southerners as a jumping off point— well-respected, yes; intelligent and insightful, yes; at least kind of wrong, yes.

Having read several of the visiting-the-New-South books, I can tell you that there is usually the propensity to spend too much time in urban areas and visit prominent leaders, journalists, and thinkers to gather their take on the region’s post-Civil Rights realities. That’s troublesome for two reasons: first, Southerners always have been, and still mostly are, a predominantly rural people, and second, most Southerners are not as broadminded as a liberal newspaper editor. To me, talking mostly to these educated, cultured, politically astute people would be like reading a great movie critic’s review instead of watching the film. Nonetheless, that’s what Murray does by beginning in Greensboro, North Carolina then going next to Atlanta. Essentially, he begins by going South to a very new place.

Despite my chagrin about that, the pages of these chapters in my copy are all marked up with notes and underlined passages. In North Carolina, newspaper editor Jonathon Daniels gets much of Murray’s attention. (This is Jonathon W. Daniels of the News and Observer, not the Jonathon Daniels who was killed in Hayneville, Alabama in 1965.) Another issue is something that Murray calls “black mammy-ness,” which has to do with how so many Southern whites who professed the racist creed also proclaimed deep affection for the black women who had raised them in childhood— a hard thing to reconcile indeed. By this time, he also launched into his familiar refrain against the social sciences, which had then-recently attempted to describe the condition of black people in America, inaccurately if you ask Murray. Much of the chapter is devoted to riffing on a number of ideas: white liberals, education, risk and safety, the past versus the present, hypocrisy, William Faulkner. Uncle Remus. (One thing that is difficult about his writing is the way that he moves among subjects, making connections among seemingly disparate bits of information, so summarizing a Murray text is a tenuous task.) In the end, the subject is fallacies: the Scenic Fallacy, the Sambo Fallacy, the Minority-Group Psyche Fallacy, the Self-Image Fallacy. As with The Omni-Americans, Murray is particularly concerned with the popular explanations – let’s call them narratives here – that he believes are wrongheaded— so we’ll call them myths. One among them, relating to the Minority-Group Psyche Fallacy, he writes to point out a contradiction: “You can’t be ignorant of the world at large and overimpressed by it at the same time.”

By the time Murray gets to Atlanta, he finds that this “City Too Busy to Hate” has “improved only up to a point.” Staying in a hotel on Peachtreet Street, he marvels at the fact that he wouldn’t have been allowed to stay there in earlier times. Does that mean that “stiff white resistance” is over? No. He goes on to make vague allusions to “legal and political trickery” and to the “credibility gap.” Ultimately, he tells us, “I’m not here to run any statistics but to see how it feels.”

Of course, in Atlanta, a writer in his position can’t – and shouldn’t, and wouldn’t – ignore Martin Luther King, Jr’s legacy, and Murray uses the man as a jumping off point to riff once again about change: who creates it, who assesses it, who actually benefits. There are also reminders here, regarding King, that in an earlier time black people sought education and opportunity for the benefit of their whole community, whereas in 1970 it seemed to be about personal gain, not the betterment of the race. He also worries that King’s efforts to bring his extraordinary efforts into the minds of ordinary people will result in his humanization, which would diminish the greatness of his acts. In a world where racism and its effects were definitely not resolved, in this “now-South metropolis,” the leaders were going to need to be larger than life.

In chapter four, “Tuskegee,” Albert Murray loosens his tie, says Hold my drink, and cuts loose. His affinity for his college alma mater is obvious, and as a reader of his other works, I was glad I was ready. The chapter is full-on tour de force of his recollections. Keep in mind that he was a student there in the mid- to late 1930s, about twenty years after the death of Booker T. Washington himself and during a time well-before the Civil Rights movement. Here, we get a jazzy and spontaneous lesson about the faculty, campus life, the learning, and the wonders of his experience. Within this context, Murray does discuss “white viciousness” and its real and looming presence, but insists upon meeting it challenges with an uncompromising desire to transcend it. Midway through the chapter, he shares this bit of self-awareness:

But then such is the miraculous nature of memory and make-believe and hence the very essence of human consciousness that not only do forgetfulness and recollection go hand in hand, they are in truth indispensable to each other.

Murray is apprising us that his portrayal of Tuskegee is his own mythic narrative: based on experience not study, one part factual, one part imagined, somewhat embellished, somewhat untrue, and completely real to him.

Next is Mobile, and once again, he is staying in a hotel that never would have admitted him in earlier times: the Battle House. This time, Murray opens the chapter with a direct and blunt discussion of race and identity, getting into who is a “peckerwood,” how the term for black children used to be “darky,” and that he will always be his momma’s baby boy. What follows is a very conversational and stream-of-consciousness portion of this narrative about going back home to a “very old place.” Pages upon pages recount remembered dialogue among the people as they spout off opinions and cuss freely, blowing through their ideas about life and how it is. Here we read diatribes about how The Beatles stole their music and how Lyndon Johnson was just another white politician.

The final chapter, “New Orleans, Greenville, Memphis,” constitutes Murray’s last leg of this trip. In Louisiana, he delves into Walker Percy and block quotes a lot. Then there is some discussion of editor Hodding Carter and finally, he tries to call Shelby Foote but can’t get in touch with him. After the wild ride that the Mobile chapter is, this one feels like the hangover that follows. Murray admits that, by the time he gets to Memphis, he feels like he has already left the South.

While I like Albert Murray for his unique perspectives and no-nonsense outlook, I will freely admit that his writing isn’t easy to read. The style in The Omni-Americans, in the speeches and reviews in From the Briarpatch File, and in others of his works is reasonably tame, but South to a Very Old Place is very much a work of memory about a sense of place. It is cerebral and personal. In the writing of it, Murray employs the second-person “you” voice and utilizes italics for asides. It isn’t always clear whether he is talking to someone or about someone or about something he is imagining or quoting a passage from some book. To read this book and experience what it contains, readers have to abandon themselves and go on the ride, whatever that will entail.

Which is what myths and beliefs and narratives are all about. These things don’t always make sense, and they often wrap around each other while clinging like climbing vines to experiences, both actual and imagined. Murray tells us from the get-go what he is doing, and he reminds us at points in the book that he may be going off the rails. For example, in talking about Walker Percy, there is this long digression, then he breaks the paragraph and begins again, “At any rate . . .” When considering how we engage with narratives of the past, especially those told to us by older people about times we didn’t witness, it can be tempting to take the storyteller at his or her word. In the South, we often hear people say, My grampa told me about the time that . . . While those stories may be packed with meaning, especially for the teller, we shouldn’t put too much stock in them as factual accounts of the past. What is great about Albert Murray is that he admits that some of it might be bullshit and that some of it is probably the product of his own romantic notions about a past that he enjoyed and now prizes. What is undoubtedly most important is that he is telling us his story. Whether and what we choose to accept about it is up to us.